In a recent campaign organized by the local town office the people of Narai and surrounding villages were asked to dig out all their old photographs. The collection that was brought together provides a most graphic account of the changes that have taken place here during the last hundred years.

The hills surrounding the village drop into the backyards of the outlying houses. A hundred years ago, the hills were bare of trees, perhaps as a result of abandonment of government prohibitions on the cutting of Kiso valley trees. Today, the land is owned by individual farmers, each of whom plants trees according to his perception of the market. Until the 1960s, many farmers encouraged deciduous trees for the firewood and charcoal markets. Together, these sources supplied eight percent of the national demand for energy. The switch to propane gas, electric and solar energy, however, stimulated some farmers to switch to conifer trees which are faster growing and in demand for construction. The forest landscape has become a mix of evergreens and deciduous species, resulting in a patchwork quilt on the hill slopes surrounding Narai.

Many of the pictures are group photographs. They show the graduating classes from local schools, groups of employees inside their place of work, the volunteer fire service, a crowd at a local festival, or pictures taken to commemorate a group outing. They underline the change that has taken place. The school photograph from 1917 shows one teacher in Western clothes and boys are far more numerous than girls. Only one student has a school uniform in the new Western style. The rest are dressed in Japanese-style clothes except for three boys in the front row who proudly hold Western-style school hats on their laps. The boys all have cropped heads, instead of the older, shaven style, and the girls (only five compared to the fifteen boys) have up-to-date hair styles. All the teachers are male. Today’s school has been rebuilt in neighboring Hirasawa in a style popular at the turn of the century. It has been built of ferro-concrete instead of wood. Children are colorfully dressed and mingle familiarly with their teachers instead of keeping a respectful distance. The firemen from the early 20th century wore Western hats and, sometimes, shoes, but were otherwise dressed in fire-retardant cotton clothes their great-grandfathers would have worn. Today’s volunteer fire brigade still has a small engine, but their equipment and clothes are strictly modern and utilitarian.

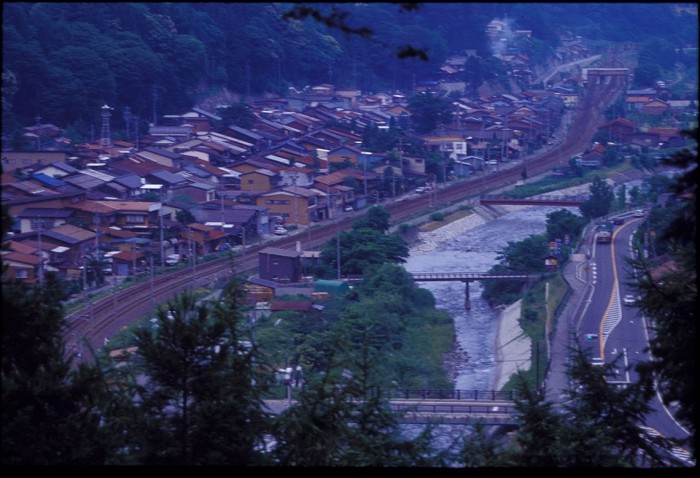

The railroad brought prosperity to the former post-towns like Narai which received stations. Construction at the turn of the century was a favorite topic for photographers. The railroad had to be squeezed in where it could fit. In some parts of the Kiso valley, it was laid directly on top of the Nakasendo, but in Narai, there was room at the back of the post-town beside the river.

The railway was the lifeline to Narai in the early 20th century; without it, the town might have nearly disappeared like so many other towns. By the 1970s, the railway was receding in importance. Tickets are now sold by machines and an employee shows up occasionally, but the really important means of transport is the road. Buses began to carry more people than trains, and private cars are now the main form of transportation.

In the early years of the Showa emperor’s reign, town festivals and youth group pictures assume pride of place, reflecting the importance of religion, particularly Shinto, in the nationalism growing in the 1930s. Today, young people are still portrayed in groups, but they are out skiing on the nearby slopes or splashing around at the swimming pool.

Around 1980, Narai, with the support of the national and prefectural governments, began to achieve recognition of the significance of the old post-town that was in danger of disappearing. Old buildings were revived, electric lines were kept away from the old Nakasendo route and tourism began to assume economic significance to the life of the community. By 1982, environmental issues also became popular and a ‘Reduce Garbage to Zero’ movement turned out a large group of supporters. The ‘revival’ and preservation of the old post-town hit a height in 1988 with the third annual staging of the Narai traditional street dance with identically clad dancers lining both sides of the Nakasendo.