In the early 1870s, a French military observer, Leon Descharmes, noted that with the invention of the rickshaw it was possible to travel the eighty miles from Takasaki to Tokyo in a single day on the existing roads. He went on to say that:

although the route may appear good at a dry season of the year, the nature of the ground clearly indicates that this same road would become heavy and often impracticable after continuous rains. The formation on this line, which opens up great commercial centers, of a macadamized road practicable for carriages in all weathers, would greatly advance the prosperity of the country.

How right he was. By the 1980s, the Shinkansen made the same distance in fifty minutes. High-speed expressways, national highways, and express commuter trains had all been developed to prove Descharmes correct. The Takasaki to Tokyo corridor is virtually fully developed now with few farms remaining between the main population centers. This is one of the areas for rapid expansion of the larger metropolitan area of Tokyo, now totaling some 30 million people in one of the most important economic and commercial urban centers on earth.

Although the modern transport systems are rapid, the traveler must line up for tickets, wait patiently on platforms, and cope with disappointment when the train is full. The same is true on the `high-speed’ expressways where the driver must queue up to enter, only to creep along elevated roadways behind long lines of bored and angry travelers.

At rush-hour, buses, taxis, and other forms of public transport offer similar frustrations. So what about the pedestrian?

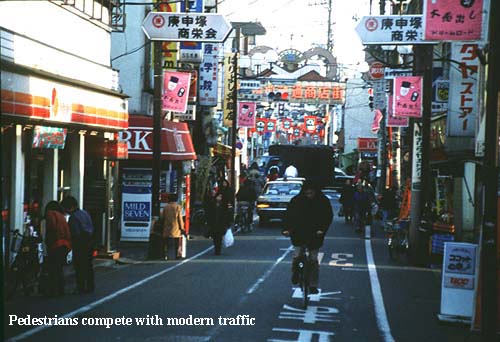

In the 17th century, the road was designed for pedestrian traffic. Today, however, scant attention is given to walkers. With luck, there is a sidewalk; the rest of the time, there is a painted line which separates the walkway from the roadway. This line is usually blocked by telephone poles, parked cars, vending machines, and other obstructions, forcing the walker into the line of passing traffic. Where there is a sidewalk, it dips and rises with each driveway into houses and businesses, threatening to turn the walker’s ankle at every opportunity. Drainage ditches lie dangerously exposed beside the sidewalk or, where they are covered with cement slabs, the regularly spaced access holes are an additional hazard, even to the wary traveler.

The Japanese have avoided these problems by using bicycles, on and off the sidewalk. They are faster than a car in rush-hour, but big enough to send pedestrians scattering to safety.

The rickshaws of Descharmes’ day are long gone, but the paved roads of today bring thousands of commuters on bicycles to the parking lots around the train stations along the old Nakasendo. The trains may be crowded, but Descharmes’ predictions of prosperity have proven perfectly accurate.