One of the most vivid descriptions of travel in 17th century Japan is provided by the Dutchman, Engelbert Kaempfer. He was a doctor attached to the Dutch East India Company, based at the island of Dejima in Nagasaki. He made the long journey to Edo twice, in 1691 and 1692, as part of the alternate residence visit made by the Dutch traders to pay their respects to the shogun. His detailed description of all aspects of these journeys are recorded in his book The History of Japan.

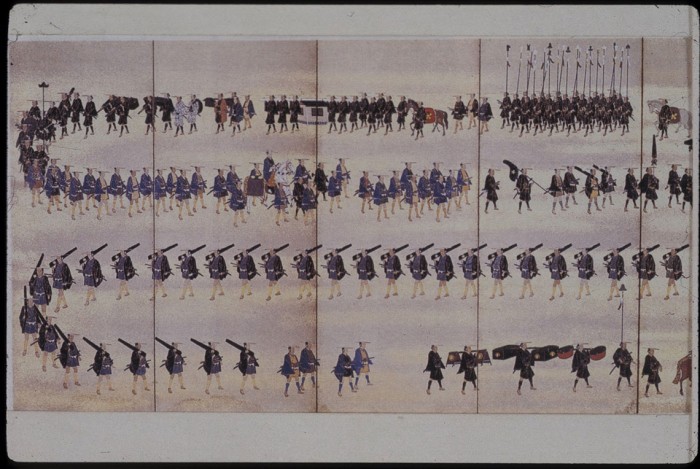

People of the highest rank, such as daimyo and court nobility, were carried for the entire length of their journey in an enclosed palanquin, or norimon. Richly adorned inside with silk cushions and hangings, the size of these lacquered norimon (and the number of footmen required to carry them) was determined by the status of the occupant. The largest required eight carriers and were spacious enough to lie down and sleep in. Small windows covered with bamboo screens allowed the occupant to see out but prevented onlookers peering inside. Few would dare such an invasion of privacy anyway, since all other people on the road were expected to move aside and avert their gaze by bowing to the ground when a norimon approached. Retainers, who were normally armed and marching on either side of the norimon, ensured everyone conformed to this rule.

At regular intervals along the road temporary huts of green leafed branches were erected for the convenience of high ranking officials, should the need arise. The road was swept by broom just ahead of important processions, and sand was sprinkled on the road if it rained. In general, therefore, the roads always had a neat and tidy appearance. The local villagers who had the task of maintaining the road in their area are said to have benefited from this responsibility. The pine leaves and discarded straw sandals and other rubbish provided a useful source of fuel, while horse dung and other excrement was collected for spreading on the fields.

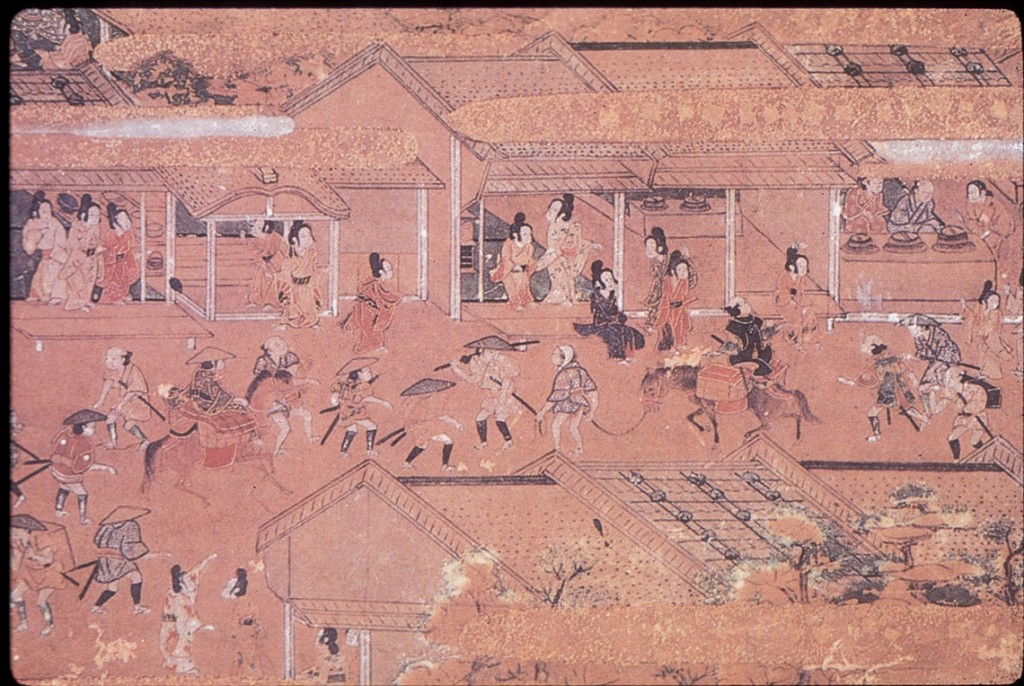

Well-to-do travelers of lower rank were denied the privilege of being carried in a norimon, and so generally journeyed on horseback. Riding ‘Western-style’ was discouraged, however, since this was considered too warlike and only appropriate for armed samurai. Instead, travelers rode on pack-horses, sitting cross-legged atop two wooden panniers slung either side of the saddle. Personal bedding was usually spread over the panniers and horse’s back, to provide some degree of comfort to the rider.

Holding the two panniers together was another wooden box strapped behind the horse’s neck. This could be opened easily by the rider, and so was generally used to keep things which might be required during the journey. Such items might include a fan, on the back of which a route-map or local travel guide might be printed. Also it would contain cash for small expenditures, tied together on a piece of string through the square holes in each coin. Another essential item of travel equipment was a pair of straw sandals (waraji), to be used in case the traveler had to get off the horse and walk. The horses were also shod in straw ‘shoes’ and many spare sets had to be kept because they wore out so quickly.

Horses were held at the bridle by a footman, so that the party never traveled faster than a walking pace. Climbing or descending steep passes was considered too difficult and dangerous for horseback riding, so porters were usually hired to carry the baggage on these sections. If the traveler chose not to walk himself, he could hire a kago. This was a commoner’s version of a norimon, being a simple, cramped seat slung under a pole and carried by two porters. If it rained the kago could be covered over by a water-proofed oiled paper cape. The porters, who were usually very scantily clad, could protect themselves from the rain with capes made of straw.

Kaempfer describes the great highways, even in the 1690s, as being extremely crowded: ‘. . .upon some days more crowded than the public streets in any of the most populous towns in Europe’. Apart from the people of high rank and their huge retinues of soldiers and porters, and other travelers who could afford to be carried on horseback or in a kago, there was also a large volume of pedestrian traffic on the roads. Such travelers included small groups of pilgrims and others, such as touring players, making long distance journeys for a specific purpose. There were also express messengers on official business, for whom everyone on the road had to give way. Much of the traffic was local, however, and included many people who earned their living ‘working the roads’.

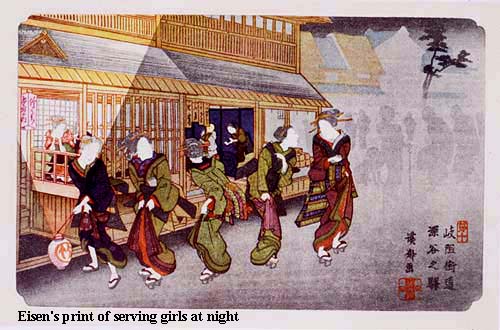

Perhaps the most unusual of these people were young girls of great beauty who had shaven their heads and taken up religious orders as nuns (bikuni). Wearing hoods of black silk, Kaempfer describes them as ‘by much the handsomest girls we saw in Japan’ though ‘very little religious blood seems to circulate in their veins’. Often formerly employed as tea-house ‘wenches’ these girls, usually from a poor rural background, had purchased the privilege of becoming nuns and now earned a living by ‘begging’. Waiting at the roadside for travelers with money to pass by, they would join such travelers, offering ‘companionship’. Singing songs or engaging in polite and demure conversation, they might often accompany travelers for a few miles in return for cash placed in their begging bowls. However, as Kaempfer dryly observes ‘. . . not to extol their modesty beyond what it deserves . . . they make nothing of laying their bosoms quite bare to the view of charitable travelers all the while they keep them company’.

Once past her prime, a bikuni might marry a priest who also made a living by begging on the roads. The priest’s methods of extorting money were very different to those of the nun, as Kaempfer notes at length:

They carry their children along with them upon the same begging errand, clad like their fathers, but with their heads shav’d. These little bastards are exceedingly troublesome and importunate with travelers, and commonly take care to light of them, as they are going up some hill or mountain, where because of the difficult ascent they cannot well escape, nor indeed otherwise get rid of them without giving them something. In some places they and their fathers accost travelers in company with a group of Bikuni’s, and with their rattling, singing, trumpeting, chattering, and crying, make such a horrid frightful noise, as would make one mad or deaf.

Indeed, it seems travel along the highways in the 17th century was often troublesome. In addition to ‘numberless other common beggars, some sick, some stout and lusty enough’, there was a continual cry of hawkers and children following travelers with goods to sell. The journey from Kyoto to Edo was long and hard, but with such constant annoyance on the way it seems no wonder that travelers kept moving as speedily as possible. Averaging 25 to 30 miles a day, travelers usually completed the journey in about two weeks.